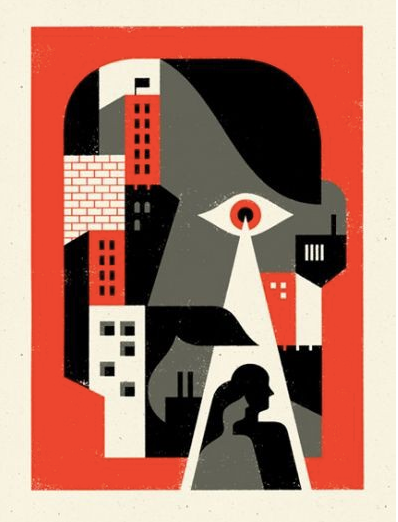

Our institutional engagement on privacy demonstrates a capacity gap

Facebook’s motto was, “move fast and break things”. By now we have all heard various variations of it to mock the social networking platform which has become a global brand for privacy breaches and misinformation campaigns — even interfering in the election processes of major democracies. The latest in this torrent of disclosures is the investigation by the New York Times which has documented a range of private deals struck by Facebook for the reciprocal sharing of user data with the knowledge of top management. Some deals permitted access even to your private chats. But rather than merely documenting a violation of user trust by Facebook, which has received extensive commentary, let us focus on walking towards solutions. Are we any closer to them?

Here, it is important to consider the response by the Indian government. It has been pandering to a cycle of social media outrage. One which follows a predictable, brightly painted path which leads to a dead end for remedies and positive outcomes. The underlying cause for our deficient national response either illustrates a complete absence of institutions, or a lack of capacity in the existing. Let us first limit ourselves to data protection and privacy and go instance by an instance which evidences a clear trend of the Government response best described by the motto, “move slow and calm things”.

Scandals first go unnoticed

Even prior to the disclosures by Cambridge Analytica, Facebook was in the crosshairs of the Indian civil society activists who fought against it in the very publicly on net neutrality. One of the measures attempted by the company was to offer users without internet on their phones, a platform called, “Free Basics”, where a bouquet of essential websites. In December 2015 it argued that by facilitating access to websites beyond Facebook it’s intent was purely altruistic. At that very point, this deal was opposed on grounds of net neutrality by those who recognised that Facebook would become a gatekeeper to the internet. The opposition to, “Free Basics”, won with a ban on it being imposed by the Telecom Regulator. However, one subsidiary argument which largely went unnoticed was that Facebook was not clearly stating how it would use the personal data of users who used the Free Basics platform. While three years ago, when the net neutrality campaign was in full bloom this may have seen as a distant fear, today there is a clear realisation that this was a reasonable inference. At that time, and as on date, there is no data protection authority or the office of a privacy commissioner to investigate and independently audit the Free Basics platform.

Undaunted Facebook continued its corporate blitzkrieg building a digital conglomerate. These were primarily through acquisitions but also data sharing practices, in which any application which got access to Facebook data, had to share it back with Facebook. This philosophy of data hoarding became clear when it after acquiring Whatsapp changed its privacy policy with effect from September 2016. It allowed data sharing between Whatsapp and Facebook of a users metadata, without clearly explaining what was being shared and how it was being used. Changes to these terms of service were challenged in a public interest petition in the High Court of Delhi which dismissed this legal challenge, among other things noting that at the time the status of the fundamental right to privacy was disputed based on an objection by the Central Government.

The decision of the High Court was appealed to the Supreme Court sensed seriousness in this plea and formed a constitution bench. When in August 2017 the right to privacy judgement came there was a hope that it could result in greater accountability with the horizontal application to private platforms such as Whatsapp and Facebook. Instead, as documented in order in September 2017 the Union Government submitted it had constituted a data protection authority headed by retired Supreme Court judge Justice B.N. Srikrishna on the same issue. In sense, pushing for a deferral of the hearing. As on date, the Whatsapp-Facebook case is still pending in the Supreme Court. There is little hope for active hearings given it requires a constitution bench of the higher numerical strength of judges to be specially constituted.

A shabby response on Cambridge Analytica

By March 2018 the Cambridge Analytica press stories which began as reports of political contracts rose into a press maelstrom. Blockbuster reports by the New York Times and the Observer documented the use of personal data of Facebook users for micro-targeting them with advertisements with subtle forms of political campaigning without their knowledge. The claim was this influenced their voting preferences and the outcome of elections.

This immediately gained a cynical hue in India, with a whodunnit approach in which petty and personal allegations flew in television debates. Suspicion pointed to the Indian National Congress as per the statement of Christopher Wylie, the Cambridge Analytica whistleblower. Meanwhile, the Government through the Ministry of Electronics and IT responded in two principal ways. It first wrote letters to Facebook the complete text and responses to it were not made public. Secondly, there were strongly worded press interactions which included ministerial statements to summon Mark Zuckerberg to India.

Concurrently the Parliamentary Standing Committee on IT in April 2018 also started examining this issue. While it did invite public comments, its proceedings, outcomes and schedule have not been disclosed citing parliamentary procedure. Subsequently, the matter at the ministerial level was referred to the Central Bureau of Investigation which launched a preliminary investigation in September 2018. Till date, there is little public information on positive movement in this investigation. We know little on how Indians were impacted beyond the unexamined statistic that 562,000 Indians were impacted by Cambridge Analytica. High on emotion and rhetoric, there is little to show in terms of results.

Public welfare requires public institutions

Let us remember many of these problems go much beyond Facebook, to the entire wave of digitisation posing a radical change from the big building blocks down to a fine grain of Indian society. Who will guarantee that such changes serve public welfare? Not, facebook. This task must fall to public institutions. This seems unlikely at present.

Movement on a privacy law has become gridlocked in recent months. A draft law to safeguard it is beset with controversy in a closed drafting process without much transparency. It has no clear path to enactment and is not listed for the ongoing winter session of parliament. On the other hand, the government has prioritised more data collection and privacy impairing legislations. These include the DNA Regulation Bill which is listed for discussion and voting, accorded cabinet approval for amendments related to Aadhaar. Let us even imagine a hypothetical that such priorities change, and by a stroke of luck, we get a Data Protection law. It will still matter what is the form and detail present within it. Will it protect us? Take for instance the transitory provisions which permit the government to delay notification for 3 years. Imagine a law passed by parliament today, completely coming into force only by the end in December 2021! It will be delaying the administration of a remedy and imperilling the health of the Indian republic despite a clear diagnosis.

Government must act with urgency. While we should continue focusing scrutiny on large platforms such as Facebook, it cannot be done by the smarts and technical negotiations of everyday users. Large platforms can only be corporally punished, not rationally reformed by Governments which lack the institutional capacity for the specific harms caused by them. We must not forget that Facebook, despite its unethical conduct serves enduring value to millions of Indians. To properly harness digitisation we now have the challenge to develop and prioritise institutions of governance to safeguard users. This must start immediately with a strong, rights protecting, comprehensive privacy law. At present, India despite having the second highest numbers of internet users in the world has little to show as a country either in investigatory outcomes, measured regulatory responses or parliamentary processes which safeguard users. Regretfully, unless things change dramatically even the most recent revelations at best will lead to statements of empty bombast and bluster. Now is the time to, “move fast and fix things”.

Apar Gupta is the Executive Director of the Internet Freedom Foundation. An edited version of this article was published in The Hindu on December 21, 2018.